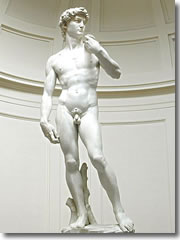

Michelangelo's David (1501–04).Many visitors come to Florence and don't care about the Uffizi or the Duomo. They just have one question on their lips "Which way to the David?"

The Accademia Galleries contain many paintings (by Perugino, Botticelli, Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo, etc.), and Giambologna's plaster study for the Rape of the Sabines, but most people come here for one thing only.

In 1501 Michelangelo took an enormous piece of marble that a previous sculptor had chipped at before declaring it unworkable, and by 1504 turned it into a Goliath-sized David, a masterpiece of the male nude so realistic, so classically lifelike—shifting its weight onto one leg and holding its sling nonchalantly on its shoulder—that it completely changed the way in which people thought about sculpting the human body.

Michelangelo's David

The first long hall is devoted to Michelangelo and, though you pass his Slaves and the entrance to the painting gallery, most visitors are immediately drawn down to the far end, a tribune dominated by the most famous sculpture in the world: Michelangelo's David ★★★.

A hot young sculptor fresh from his success with the Pietà in Rome, Michelangelo offered in 1501 to take on a slab of marble that had already been worked on by another sculptor (who had taken a chunk out of one side before declaring it too strangely shaped to use).

The huge slab had been lying around the Duomo's workyards so long it earned a nickname, Il Gigante (the Giant), so it was with a twist of humor that Michelangelo, only 29 years old, finished in 1504 a Goliath-size David for the city.

There was originally a vague idea that the statue would become part of the Duomo, but Florence's republican government soon wheeled it down to stand on Piazza della Signoria in front of the Palazzo Vecchio to symbolize the defeated tyranny of the Medici, who had been ousted a decade before (but would return with a vengeance).

During a 1527 anti-Medicean siege on the palazzo, a bench thrown at the attackers from one of the windows hit David's left arm, which reportedly came crashing down on a farmer's toe. (A young Giorgio Vasari came scurrying out to gather all the pieces for safekeeping, despite the riot going on around him, and the arm was later reconstituted.)

Even the sculpture's 1873 removal to the Accademia to save it from the elements (a copy stands in its place) hasn't kept it entirely safe—in 1991, a man threw himself on the statue and began hammering at the right foot, dislodging several toes. The foot was repaired, and David's Plexiglas shield went up.

It's funny. If you look at the replica David at Palazzo Vecchio, he looks—indeed—small, a lithe youth ready for acion. Crammed inside the room like this, though, he looks a little over-large, giving the piece an oafish air.

Michelangelo'sSlaves and St. Matthew

The gallery of nonfiniti Slaves and The David at the Accademia. (Photo by Darren Milligan)

The hall leading up to David is lined with perhaps Michelangelo's most fascinating works, the four famous nonfiniti ("unfinished") Slaves,or Prisoners ★★★—to many people more interesting than the David itself.

These Slaves are in varying degrees of being worked on, and give a critical insight into how Michelangelo approached his craft—chipping away first at the abdomen, going for the gut of the sculpture and bringing that to life first so it could tell him how the rest should start to take form before moving on to rough out limbs and faces.

Like no others, these statues symbolize Michelangelo's theory that sculpture is an "art that takes away superfluous material." The great master saw a true sculpture as something that was already inherent in the stone, and all it needed was a skilled chisel to free it from the extraneous rock.

Whether he intended the statues to look the way they do now or in fact left them only half done has been debated by art historians to exhaustion. Originally intended for a grand tomb of Pope Julius II (who had commissioned the famous Sistine Chapel ceiling, and whose actual finished tomb in Rome does at least contain Michelangelo's Moses), the Slaves were for a long while installed in a faux grotto in the Medici's Boboli Gardens behind the Pitti Palace.

The result, no matter what the sculptor's intentions, is remarkable, a symbol of the master's great art and personal views on craft as his Slaves struggle to break free of their chipped stone prisons.

Nearby, in a similar mode, is a statue of St. Matthew ★★ Michelangelo began carving (1504–08) as part of a series of Apostles he was at one point going to complete for the Duomo.

The Palestrina Pietà at the end of the corridor on the right was long attributed to Michelangelo but most scholars now believe it is the work of his students.

Some of the amazing, largely ignored Accademia works not by Michelangelo

Off this hall of Slaves is the first wing of the painting gallery, which includes a panel, possibly from a wedding chest, known as the Cassone Adimari ★, painted by Lo Scheggia in the 1440s. It shows the happy couple's promenade to the Duomo, with the green-and-white marbles of the Baptistery prominent in the background.

A number of 15th- and 16th-century Florentine artists are here; search out the Madonna del Mare (Madonna of the Sea) attributed to Botticelli or his student Filippino Lippi.

In the wings off David's tribune are large paintings by Michelangelo's contemporaries and immediate artistic heirs, mannerists over whom he had a very strong influence—they even say Michelangelo provided the original drawing from which Pontormo painted his amorous Venus and Cupid.

Off the end of the left wing is a long 19th-century hall crowded wall to wall and stacked floor to ceiling with plaster casts of hundreds of sculptures and busts—the Accademia, after all, is what it sounds like: an academy for budding young artists, founded in 1784 as an offshoot of the Academy of Art Design that dates from Michelangelo's time (1565).