Subscribe to the blog

|

|

|

|

|

|

Find a Flight Consider a Consolidator Rent a Car Pick a Railpass Book a Vacation Reserve a Room Get Gear |

|

||||||

|

Brindisi,

Waiting Room of the Aegean Brindisi is, and always has been, a ferry port. From the days when the Romans extended the Via Appia here from Rome through medieval knights leaving for the Crusades to modern sun-seekers on their way to the Greek Isles, it's been where you step off the road and onto the high seas. Brindisi is the only Italian town where more road signs point to "Greece" than to anywhere in Italy. The passeggiata here is less an evening stroll than a parade of backpackers, ferry-bound tourists awaiting their 10pm departure by restlessly marching up and down the main drag, their eyes sparkling with visions of Greek islands, their faces grimacing as they bite into what very well may be the worst pizza-by-the-slice this side of Naples. There is little to see in Brindisi, but I am determined to find something to amuse the legions of folks who are stuck here daily, killing time before they can board the slow boat to Greece. Brindisi was settled in the 6th century BC by the Messapians (who dubbed it Brunda, or "stag's head," after the antlery shape of its branching harbor), and later became a Greek colony that evolved into the Latin port of Brindisium. But it didn't really boom until in the AD 2nd century, when the Via Appia was finished. The Appian Way is one of Europe's oldest highways, famous for that mass crucifixion scene at the end of Spartacus and for the catacombs that line the road at the Rome end. Though most of it is now clad in asphalt, stretches of the Via Appia's worn ancient paving stones are still preserved all along its route--terribly scenic, but hell to ride a bike over; trust me. This road was once pounded by the Roman legions off to conquer, patrol, and defend the Empire. But first they had to pass through Brindisi. This is where Julius Caesar tried to hem in Pompey's ships in 49 BC, and where Octavian (later to become Augustus) made a famed but short-lived peace treaty with Marc Antony. Virgil traveled all the way to Greece to submit his manuscript for the nationalistic epic Aeneid to a campaigning Augustus, but fell ill while there. He managed to make it to Brindisium to convalesce, but was dead within three days. Though he demanded on his deathbed that his manuscript be destroyed, Augustus overruled him—to the dismay of Latin students for millennia to come—edited out the bits he didn't like, and published it anyway (isn't that just like an emperor? Or a publisher?). Another great Roman scribe, Horace, even dabbled in a bit of my trade when he penned his fifth Satire about a road trip here with his buddy Maecenas in 38 BC (during which he got a raging case of la turista from the water in Campagna). more >> Copyright © 1998 by Reid Bramblett |

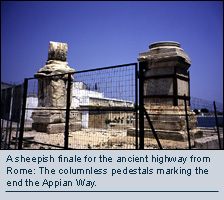

Sadly,

little of this Roman history is evident anymore. I read about a pair

of ancient Roman columns that mark the end of the Appian Way, towering

over the short staircase leading down to the waterfront esplanade. When

I get to the end of Via Colonna, the final stretch of the Appian Way,

I am disappointed to find nothing but a pair of stumps. One pillar was

struck by lightning and toppled in 1528. (Brindisi sold it to Lecce,

which still uses it to prop up a statue of their patron saint on the

main piazza.) The remaining column was recently spirited away for restoration.

Only their pedestals remain, marked with graffiti, behind a low fence.

Sadly,

little of this Roman history is evident anymore. I read about a pair

of ancient Roman columns that mark the end of the Appian Way, towering

over the short staircase leading down to the waterfront esplanade. When

I get to the end of Via Colonna, the final stretch of the Appian Way,

I am disappointed to find nothing but a pair of stumps. One pillar was

struck by lightning and toppled in 1528. (Brindisi sold it to Lecce,

which still uses it to prop up a statue of their patron saint on the

main piazza.) The remaining column was recently spirited away for restoration.

Only their pedestals remain, marked with graffiti, behind a low fence.